Radiowcy sekcji rosyjskiej Głosu Ameryki 1948

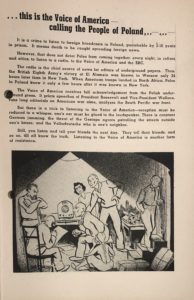

Pracownicy sekcji rosyjskiej Głosu Ameryki z około 1948 roku zostali uwidocznieni na zdjęciu w studio rozgłośni w Nowym Jorku przez Associated Press. Według AP, byli nimi Boris Bodenov (autor tekstów radiowych), Alexander Frankley (redaktor w dziale rosyjskim) i Tatiana Hecker (autorka tekstów i spikerka). AP wyjaśnił, że napis na mikrofonie w języku rosyjskim oznaczał „Głos Ameryki”, ale dosłownym tłumaczeniem z rosyjskiego byłoby „Głos Stanów Zjednoczonych Ameryki”. Angielskojęzyczny napis drugim mikrofonie, „THE VOICE OF AMERICA”, to „GŁOS AMERYKI” po polsku.

Nazwa „Głos Ameryki” pojawiła się oficjalnie dopiero po wojnie, gdyż wcześniej programy amerykańskiej rozgłośni rządowej od chwili jej założenia w 1942 roku były zapowiadane pod różnymi innymi nazwami. Przez jakiś czas zaraz po wojnie używano oficjalnie nazwy „Głos Stanów Zjednoczonych Ameryki.” Według przypuszczeń, nieoficjalne użycie nazwy „Głos Ameryki” (Voice of America) pojawiło się w druku po raz pierwszy w 1943 roku w socjalistycznej broszurze propagandowej wydanej w Stanach Zjednoczonych przez pracowników działu polskiego Biura Informacji Wojennej (Office of War Information – OWI), w ramach którego działał Głos Ameryki. Jednym z tych pracowników był Stefan Arski, znany również jako Artur Salman. Arski zrezygnował z pracy w Głosie Ameryki w 1947 roku i powrócił do Polski, gdzie wstąpił do PZPR i stał się jednym z głównych antyamerykańskich propagandystów reżimu PRL.

Sekcja rosyjska Głosu Ameryki powstała dopiero w 1947 roku ponieważ wcześniej prosowieckie kierownictwo rozgłośni prawdopodobnie obawiało się, że rosyjskojęzyczne audycje mogłyby drażnić Stalina, głównego sojusznika Stanów Zjednoczonych w wojnie z hitlerowskimi Niemcami. Negatywne informacje o Rosji sowieckiej cenzurował w czasie wojny Howard Fast, pierwszy szef centralnego działu wiadomości Głosu Ameryki, który wstąpił do Partii Komunistycznej USA na krótko przed rezygnacją z pracy w rozgłośni w 1944 roku. W 1953 roku Fast został wyróżniony Międzynarodową Nagrodą Pokojową im. Stalina. Amerykański autor potępił stalinizm w 1956 roku i zerwał związki z Partią Komunistyczną USA, ale nie krytykował komunizmu i większości posunięć postalinowskich władz ZSSR z wyjątkiem stłumienia powstania węgierskiego w 1956 roku. Niektóre książki Fasta tłumaczyła w Polsce była dziennikarka Głosu Ameryki Mira Michałowska (wcześniej Zandel i Złotowska), która po powrocie do Polski ze Stanów Zjednoczonych wyszła za mąż za komunistycznego dyplomatę i była autorką popularnych artykułów prasowych i książek.

“Radio Broadcast Sent To Russia By State Department” photograph from the National Archives, Harry S. Truman Library and Museum. Description: Interior view of seven men and women taken during a radio broadcast sent to Russia from the State Department’s studios in New York. Identified as left to right: Boris Brodenov, Kathrine Elene, James Shigorin, Vladmir Postman, Mrs. Lucy Bates, Victor Franzusoff, and Mrs. Tatiana Hecker, all American citizens. Lettering on top of microphone is in Russian language. (Charles Thayer supervised the programs.) Date(s): ca. February 1947.

W początkowych latach audycji rosyjskich Głosu Ameryki unikano krytyki ZSSR i komunizmu.

Pierwszym kierownikiem sekcji rosyjskiej był Charles W. Thayer, dyplomata w Departamencie Stanu i późniejszy dyrektor Głosu Ameryki (1948-1949). Według innego dyplomaty amerykańskiego, Chestera H. Opala, Thayer nie był przekonany, że sprawcami mordu katyńskiego było sowieckie NKWD na polecenie Stalina i Biura Politycznego Partii Komunistycznej ZSSR.

Profil audycji sekcji rosyjskiej i innych programów Głosu Ameryki uległ zmianie w końcowych latach administracji prezydenta Trumana w miarę pogłębiania się zimnej wojny. Aleksandr Grigorjewicz Barmin (Barmine), były funkcjonariusz wywiadu wojskowego ZSRR (Razwiedupr) i emigracyjny działacz antykomunistyczny, rozpoczął pracę w Głosie Ameryki w 1948 roku i wkrótce został kierownikiem sekcji rosyjskiej.

Po okresie względnej swobody programowej, częściowa cenzura i restrykcje w celu złagodzenia krytyki władz sowieckich powróciły już w poźniejszych latach administracji prezydenta Eisehowera. Pod rządami prezydentów Nixona, Forda, i Cartera, kierownictwo Głosu Ameryki wykonujące polecenia kierownictwa Agencji Informacyjnej Stanów Zjednoczonych (United States Information Agency – USIA), której podlegała w tym czasie rozgłośnia, ograniczyło nadawanie obszernych fragmentów z książek Aleksandra Sołżenicyna i zakazało dziennikarzom sekcji rosyjskiej przeprowadzania wywiadów z laureatem literackiej Nagrody Nobla i autorem Archipelagu GUŁag. Te ograniczenia i zakazy, które nie obowiązywały w Radiu Wolna Europa i w Radiu Swoboda, zniesiono w Głosie Ameryki dopiero w czasie administracji prezydenta Reagana.

Pracownicy sekcji rosyjskiej Głosu Ameryki circa 1948 r. w fotografii Associated Press, zidentyfikowani przez AP jako Boris Bodenov, Alexander Frankley i Tatiana Hecker.

The photograph by the Associated Press depicts Russian Service of the Voice of America employees, circa 1948, in the VOA New York radio studio. The journalists are identified as Boris Bodenov (writer), Alexander Frankley (editor in the Russian section), and Tatiana Hecker (writer and announcer). According to AP, the microphone inscription in Russian reads “Voice of America,” although a direct translation would be “The Voice of the United States of America.” The sign on the second microphone reads “THE VOICE OF AMERICA,” which was adopted as the station’s official name by then.

Interestingly, when the station was founded in 1942, it did not go by the name “Voice of America” but used various names for its wartime programs. The “Voice of the United States of America” was officially used for some time after the war before “Voice of America” became the official name. According to current research, the unofficial use of “Voice of America” first appeared in print in 1943 in a socialist propaganda brochure published in the United States by employees of the Polish department of the Office of War Information (OWI), under which VOA operated. One of these employees was Stefan Arski, also known as Artur Salman. Arski resigned from his work at the Voice of America in 1947 and returned to Poland, where he became one of the leading anti-American propagandists of the communist regime.

Interestingly, when the station was founded in 1942, it did not go by the name “Voice of America” but used various names for its wartime programs. The “Voice of the United States of America” was officially used for some time after the war before “Voice of America” became the official name. According to current research, the unofficial use of “Voice of America” first appeared in print in 1943 in a socialist propaganda brochure published in the United States by employees of the Polish department of the Office of War Information (OWI), under which VOA operated. One of these employees was Stefan Arski, also known as Artur Salman. Arski resigned from his work at the Voice of America in 1947 and returned to Poland, where he became one of the leading anti-American propagandists of the communist regime.

It is worth noting that the Russian Service of the Voice of America was not established until 1947, likely because the pro-Soviet station management feared Russian-language broadcasts might irritate Stalin, America’s main ally in the war against Nazi Germany. Negative information about Soviet Russia was censored during the war by Howard Fast, the first head of the Voice of America’s central news department. He joined the Communist Party USA shortly before resigning from the station in 1944. Fast was awarded the Stalin Peace Prize in 1953. The American author condemned Stalinism in 1956 and severed ties with the Communist Party USA. Still, he did not criticize communism and, except for the Soviet invasion of Hungary, the post-Stalinist USSR authorities. Some of Fast’s books were translated in Poland by the former journalist of the Voice of America, Mira Michałowska (previously Zandel and Złotowska), who, after returning to Poland from the United States, married a communist diplomat and became the author of popular press articles and books.

Initially, the Russian broadcasts of the Voice of America avoided criticism of the USSR and communism.

The first head of the Russian Service was Charles W. Thayer, a diplomat at the State Department who later became director of the Voice of America (1948-1949). According to another American diplomat, Chester H. Opal, Thayer was not convinced that the Russians were the perpetrators of the Katyn massacre. However, as the Cold War deepened, the programs’ profile changed in the Truman administration’s closing years. Aleksandr Grigorievich Barmine, a former USSR military intelligence officer and anti-communist activist in exile, started working for Voice of America in 1948 and soon became head of the Russian Service.

After a period of relative programming freedom, partial censorship and restrictions were imposed to mitigate criticism of the Soviet authorities. These limitations returned already in the later years of President Eisenhower’s administration. During the presidencies of Nixon, Ford, and Carter, the leadership of Voice of America, following the directives of the United States Information Agency (USIA), which oversaw the station at that time, restricted readings of extensive excerpts from the works of Alexander Solzhenitsyn and forbade Russian section journalists from conducting interviews with the Nobel Prize-winning author of The Gulag Archipelago. These restrictions and bans, which did not apply to Radio Free Europe and Radio Liberty, were lifted at the Voice of America during President Reagan’s administration.